A short – but critical – piece on New Age Religious Movements and some possible reasons for their emergence and popularity in postmodernity…

Melton (2001) suggests “the term New Age refers to a wave of religious enthusiasm that emerged in the 1970s” which, for Cowan (2003), have two defining characteristics:

1. NAMs represent new ways of “doing religion” and “being religious”, with the focus on finding solutions to individual and social problems through “personal transformations”; the individual must change their life in some way. In this respect Brown (2004) notes NAMs focused specifically around “transformations of the self and society”, include:

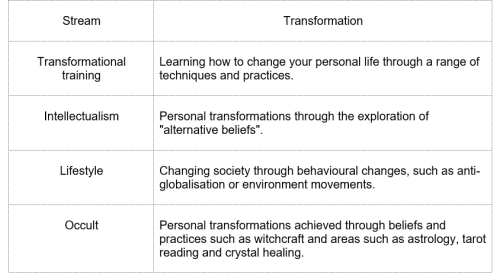

Langone (1993) identifies four main “streams” within NAMs involving different ways to “transform the self” through personal lifestyle changes.

These categories may at times overlap – occult practices might involve beliefs about lifestyle changes – but one feature common to all NAMs is the belief “spiritual knowledge and power can be achieved through the discovery of the proper techniques”.

2. Spiritual consumption involves the idea that rather than being members or believers people are consumers who “shop for spirituality”; a search for personal salvation expressed, Cowan argues, through various individual preoccupations and concerns:

This type of what Cimino and Lattin (2002) call “shopping for faith” or religious consumerism is, for Fraser (2005), one that “Offers a language for the divine that dispenses with all the off-putting paraphernalia of priests and church; it’s about not believing in anything too specific, other than some nebulous sense of otherness or presence. It offers God without dogma”.

Brown similarly suggests NAM adherents are “less inclined to accept the personal compromises needed to maintain a stable group”, something that gives NAMs the appearance of “consumerist movements”; loose collections of individuals, engaging in spiritual shopping, whose most cohesive feature is the desire, often literally, to buy into a particular belief system.

The relatively superficial concerns of NAMs contrast with what Troeltsch (1931) calls the “asceticism of the Church”; the practice of a strict self-discipline that uses abstinence and austerity for spiritual benefit. Where asceticism is a means of acquiring virtue and self-knowledge through personal trials, denial and suffering, NAMs simple involve purchasing personal fulfilment as painlessly as possible.

Graham (2004), for example, describes how “Shopping for Kabbalah is the newest new age mantra of anyone who wants to attach themselves to the craze, but doesn’t necessarily want to invest years in earnest study. While most of us will never fully appreciate the intimacies of the ancient mystical Jewish religion, enthusiastic consumers often argue that the ritual and the ecstasy of shopping is nothing short of a religious experience“. Kabbalah, in common with other forms of New Age religion, fits the postmodern condition perfectly because it involves little:

Sedgwick (2004), in this respect, sees NAMs as a reflection of the individualistic tendencies of postmodern society; people “want the feel-good factor, but not the cost of commitment. Putting it bluntly it is essentially selfish religion“.

postmodern religion?

NAMs represent a variety of beliefs and practices that are rarely, if ever, organised into a stable “community of believers”, something that epitomises a postmodern perspective and fulfils a range of requirements for a postmodern religion:

NAMs, for example, do not “speak with one voice”, outside of a general belief in “personal transformation”. Their organisational diversity makes it difficult to identify or sustain a consistent world view and their individualistic orientation, different people seeking personal solutions to their particular problems, makes the idea of a ‘New Age metanarrative’ difficult to pin down. Wide diversities within and between NAMs reflects a wider sense of fragmentation.

“Spiritual shoppers” have a massive range of available choices when looking to buy into “ready-made” solutions to their personal and social problems and this encourages a “pick-and-mix” approach; consumers pick bits they like from different NAMS (meditation, channelling, ear candling…) and mix them to create something new and personal. This suggests one feature of the “new age of religion” is the consumer experience; religion is experiential. You “go with the flow” and if it “works for you” then the rationality of the experience goes unquestioned. Consumers buy into a brand, use it as and when they want and discard it when it no longer serves its purpose.

Where a central tenet of modernity is rationality and various forms of objective testing and proof, a central condition of postmodernity is experience; as Cimino and Lattin argue:

“Whether soul-shaking experiences and religious conversions are the true action of the Holy Spirit, hypnotic trance states, or some other psychological trick makes little difference. They feel real. They inspire people to change their lives and commit themselves to another power, whether it’s a higher power outside themselves or an inner voice crying out from the depths of their soul“.

This “validation through personal experience” is a further reflection of postmodern uncertainties, just as in a different way organised religion was a reflection of pre-modern uncertainty. Langone, for example, argues “New Age mysticism” appeals to a wide range of consumer groups, particularly those searching for “meanings” traditional religions have failed to supply. New Age ideas based around magic and personal fulfilment have also found their way into modern business practices:

Bauman (1997) is particularly scathing of these new forms of spiritualism.

“Postmodernity is the era of experts in “identity problems” of personality healers, of marriage guides, of writers of “how to reassert yourself” books; it is the era of the “counselling boom”. Business executives need spiritual counselling and their organizations need spiritual healing. Uncertainty postmodern-style begets not the demand for religion but the ever rising demand for identity-experts“.

Ammerman (1997) further notes the significance of mediated religious influences such as books, magazines, television and, increasingly, the internet that “provide models of behaviour, pieces of rhetoric, bits of belief, from which individuals construct the routines they enact“.

While Roof (1996) refers to this tendency as “pastiche religion”, something that reflects its fundamental character as an individual “construction”, others have characterised NAMs as bricolage religions; different bits and pieces drawn from various religious sources are constructed, reconstructed and combined at the hands of different individuals and groups in a patchwork of beliefs and practices.

Share This Post

Related

Discover more from ShortCutstv

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.